- Home

- David Movsesian

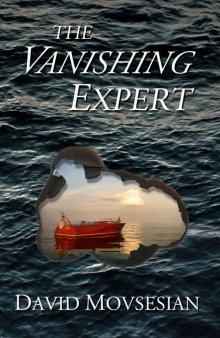

The Vanishing Expert

The Vanishing Expert Read online

THE

VANISHING

EXPERT

DAVID MOVSESIAN

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, places, events and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or used in a fictitious manner. No reference to any real person is intended or should be inferred.

Cover photograph by Matt Smith. Used by permission.

Cover design by David Movsesian

Copyright © 2015 David Movsesian

All rights reserved.

To Edward and Shirley Movsesian,

my mom and dad

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements

Lost At Sea

Love And Work

The Fatal Flaw

A Romantic Notion

Weight Of The World

A Simple Life

Gone But Not Forgotten

Leap Of Faith

The Christmas Gift

Winter

The Reunion

Discovering Eden

A Return To The Sea

A Good Night

Prodigal Son

Orphans

The Choices We Make

Saying Goodbye

Ben Jordan

The Benefactor

Means To An End

The Baby In The Hedges

The Portland Lawyer

The Wedding Tree

The Vanishing Expert

In The Presence Of Ghosts

What Speaks To Us

An Unexpected Gift

Everything’s Normal

What Comes Around

Goodnight, Rose

The First Letter

The Second Letter

A View Of The Sea

About The Author

Acknowledgements

My gratitude goes out to so many who, whether they realized it or not, had a hand in guiding me on this journey.

To my father, for all the lessons he taught me, both as a boy and as a man, many of which have found their way into this work in one form or another. While he never had the opportunity to read it, I’d like to think he would be proud, not only for the work itself, but also that so many of his lessons, and the wisdom he imparted over the years, actually stuck.

To my mother, for all her love, patience, humor, and encouragement. And for all those rainy days when I was a small boy when she would set up her old Underwood typewriter on the dining room table, and perched me atop a stack of phone books so I could peck away at the keys, putting my first stories to paper. I have no doubt that my love of writing started there.

To my remarkable wife, Lori, who has patiently suffered my obsession (and me) these last twenty-some years. Looking back, I could not have done this, or much of anything else, without her love and support.

To my sister, Sue Publicover, without whose enthusiastic encouragement this would no doubt still be one of a handful of unfinished projects.

To Joyce (Paglia) Baldassare, the first to believe in my dream of becoming a novelist back when we were teenagers. Over the years, as my life occasionally led me down other paths and my writing often fell by the wayside, it was Joyce who frequently asked me “How’s the writing coming?” as if to remind me of my dream and to set me back on track. Every writer needs a friend like her.

To Marie Paglia, Joyce’s mother, who labored through an early story of mine when I was a teenager, and, as was her way, offered far more praise than it deserved. As I complete this book, I can’t help but wish Marie, who was like a second mother to me during my teen years, could have read it. Though she might not have approved of some of it, I’d like to believe that, like my father, she would have been proud.

To Robert Maloney, my remarkable teacher at Lynnfield High School, who not only encouraged and guided me as a writer, but also introduced me to the far more difficult discipline of editing. That came in handy as I spent the last year trimming dozens of pages from the original draft. (Yes, it was actually longer.)

To Constance Hunting, my professor at the University of Maine. Constance was a poet who helped me to look at the world differently, and instilled in me an appreciation of the rhythm and the cadence of prose. She, as much as anyone, helped me to not only discover my writer’s voice, but also listen to it and to trust it.

To my early readers: Special thanks to my sister, Sue (who read it in installments over years), to my mom (who read it twice, scolding me each time for having killed off the mother before the book even began), and to Joyce (who resisted the urge to read ahead to find out how it ended, and then called me sniffling back the tears when she finally got to it in due course). There is no greater compliment! Thanks also to Annette Wetherby, Lynda Zarrow, Leanne Brunelle, Paul and Cindy LaFrance, Sherry and Malcolm Granger, Gary Young, and of course, my wonderful wife, Lori, for their time, their suggestions, and their encouragement.

To Brian and Bettye Worcester, the current owners of Sawyer’s Market in Southwest Harbor, Maine for graciously granting me permission to use the name of their wonderful establishment while keeping my fictional character (Lester “Lucky” Meeks, the benevolent butcher) intact.

To Matt Smith for generously allowing me to use his haunting image of the Chris Craft as part of the cover design.

I’m forever grateful to you all.

— DM

1

Lost At Sea

May, 1990

Of the two things Gloria Moody despised most about the ocean, the second was the smell, the suffocating stench of it. She was always sickened by the pungent aroma that swept past her delicate nose. She was repulsed by that repugnant fishiness that clung to her hair and her clothes and her fine skin. It offended her each time she licked her taut lips, which were chapped from the raw sea air on that Sunday morning in May.

But what she hated most of all about the sea— what she truly found despicable about it— was that the very things that repulsed her were exactly those qualities that drew her husband to it.

Edward Moody was pulled to the sea as if by the tug of every receding tide, always longing to feel the tremendous dip and swell beneath him. It was a longing Gloria could never understand, despite her husband’s numerous efforts at enlightening her, and it was the reason she found herself out upon that vile sea on that crisp spring morning, enduring its assault on her fragile senses, and desperately trying to fend off an overpowering feeling of dread.

Narragansett Bay wasn’t especially rough that morning. The storm that had swept across Rhode Island and out across the bay the day before had departed just before midnight, but the remnants of the thick fog that had kept them ashore earlier still clung to the surface of the water like a shroud. It was slow to dissipate even as far out as they were now— a half-mile from shore and heading out toward the open ocean. From time to time, they came upon pockets of warm air where the fog lifted, hovering just a few feet above the bow of the boat, and at those moments, Gloria Moody weighed the overwhelming urge to peer beneath the fog to search the rolling ocean before them with the equally overwhelming urge to vomit.

She was still uncertain how she’d come to be aboard that Coast Guard cruiser as it navigated a circuitous route toward the mouth of the bay. She recalled some mention of a friend of a friend pulling a string that shouldn't have been pulled, and before she knew what was happening, she'd been ushered aboard, wrapped in a heavy blanket, and sat helplessly watching as the pier receded away from the stern. She didn't want to be there, and the captain and the small crew shouldn’t have allowed her aboard as they searched for her husband’s boat. But there were a lot of things that happened that morning that shouldn’t have happened, and she felt as if she was at the m

ercy of all of it, less an active participant in the actions that were playing out around her than a stunned observer waiting to see what was to become of her when it was all finished.

At times, the boat moved swiftly and purposefully across the water, and the sudden speed, that gratifying sense of urgency, momentarily distracted Gloria from her gloom.

Finally! she would think. They must have found something!

But each sudden surge seemed to end as quickly as it had begun, and it was then, when the boat was just drifting, rising and falling upon the rolling sea, that Gloria’s stomach churned and her throat constricted as if a fist had closed around it. On the occasion that she poked her head through the rail, wanting desperately to wretch upon that foul sea, she decided that this would be the last time she would ever set foot upon a boat— any boat. It was a silent promise she would, in fact, keep.

While the sea was passable, it was that fog that made the search especially difficult. Finding her husband’s small boat in such conditions seemed almost a matter of chance. If they found it at all, they would more or less have to simply happen upon it, and that was assuming it was still afloat, which wasn’t an assumption anyone was making.

Everyone aboard that vessel that morning— all able seamen themselves with the single exception of Gloria Moody— wondered what Edward Moody had been doing out on his small boat on such rough seas the previous day. The storm may have been more severe than anyone had predicted, but if he was as experienced a sailor as his wife claimed, he should have seen it coming.

What none of them knew was how perfectly Edward Moody had seen that particular storm coming.

There still remained the fleeting hope that he’d somehow found his way ashore, perhaps on some isolated patch of beach that was still enshrouded in fog, where he’d run the boat aground to wait for the storm to pass. It was a hope they tried desperately to cling to, Gloria Moody most of all, but with every sweep of the vast bay, it was an optimism that was proving ever more elusive.

Edward Moody’s boat was a vintage 1953 Chris Craft Riviera that had belonged to his father. So many of Edward’s happiest childhood memories included that boat. So much joy echoed in its rich wood. He always remembered the first time he’d touched it as a child; the well-varnished surface of the mahogany hull, like glass beneath his small fingers, felt both warm and cold at the same time. It was a sensation that would remain with him all his life, the way most boys remember their first tentative touch of a woman’s breast.

For Edward, the feel of the polished wood, its sleek lines and its classic curves, was as sensuous as any woman. So, it was hardly surprising that, when the time finally came, he would part with his virginity aboard that boat. That it was resting upon its trailer behind the garage at the time was of little importance to him— certainly not at the time, nor later when he reminisced upon it. For decades, he’d remember the clumsy lovemaking on that summer evening of his sixteenth birthday as the single most perfect sexual experience of his life. The uncertainty of every touch and self-conscious whisper. The scent of mahogany and engine oil mixing with Madeleine Weeks’s sweet drugstore perfume. The creak of the trailer responding to each movement, threatening to betray them to his father who slept just on the other side of an open second-floor window no more than fifty feet from them.

The following morning, when Edward emerged from the house, he came upon his father standing quietly beside the trailer. He called Edward over to him, and placed his hand upon his son’s shoulder.

“Why don’t you go into the garage and get my grease gun,” he said to the boy. “I noticed this old trailer seems to be getting a little noisy of late.”

Edward felt all the air rush out of his lungs, wondering if his father had heard the sounds of his encounter with Madeleine Weeks the night before, the rhythmic creak and squeal of the rusty trailer beneath them. He averted his eyes, not wanting to meet his father’s gaze.

As Edward carefully greased every joint, his father stood aboard the boat, bouncing up and down in precisely the same rhythm as Edward’s enthusiastic humping of the night before. When Edward looked tentatively up at him, he saw the broad grin upon his father’s face. When finally the grease caused the trailer to fall silent beneath him, his father climbed down and stood beside his son, surveying the boat and the trailer before them.

“That ought to take care of it,” his father offered, matter-of-factly. He turned and began to walk away, a sly smile upon his face. “Now maybe I can get some sleep.”

After his rendezvous with Madeleine Weeks, the first of many aboard the Chris Craft, Edward considered that if he ever were to inherit the boat from his father, he would name it Mad’ Love in honor of that momentous event on his sixteenth birthday. It was a romantic notion that, like so many romantic notions, would never come to pass. His father had never named the boat, thinking that any name he could bestow upon it might somehow diminish its grace. Edward believed that nothing could possibly diminish its grace, not even a name inspired by a sixteen-year-old boy’s first clumsy act of fornication. But by the time his father finally passed it on to him, it seemed to have been predestined that the boat should remain nameless.

Long before that summer night behind the garage with Madeleine Weeks, Edward had spent some of his most memorable times aboard the Chris Craft. He always remembered the sensation of the wind and spray in his face as he and his father skimmed across the surface of Lake Winnipesaukee each summer. He learned to water ski behind that boat when he was twelve years old, his younger sister, Kate, sitting in the stern watching him while their father drove. He learned to navigate through every cove and inlet on that vast lake until he knew it so well he could do it at night with only the moon and the boat’s small spotlight to guide him. When he was fifteen, his father taught him how to troubleshoot and tune the engine, something he insisted Edward learn before he would permit the boy to take the boat out on his own. And during the spring of his senior year of high school, he helped his father refinish the boat’s fading wood, restoring it once again to the gleaming gem he’d remembered as a child when he first set eyes upon it.

Tending to the Chris Craft never seemed like work to Edward. He loved that boat, and he remembered hurrying home from school every afternoon that spring, just so he could be in its company. He reveled in the feel and the smell of it. For weeks, he spent every last hour of daylight sanding and scraping and shellacking and polishing the hull until it gleamed like new. He vividly remembered the pride he felt when his father placed his hand on his shoulder and announced that they were finally finished. And he remembered when they put it in the lake for the first time that summer. It was a ritual they had always shared, an annual rite of summer whose importance was never wasted on either of them. During the long, cold New England winters, it was a treasured moment that always loomed in the distance like a prize.

The boat was not only a cherished memento of his childhood, but it was also the most prized possession of his adult life, and it represented every rite of passage from one to the other. Nearly every memory he had of that boat included his father— with the obvious exception of his nights with Madeleine Weeks— and he remembered how bittersweet was the moment when his father finally gave it to him after suffering his first stroke in 1987, just three years before Edward’s disappearance. It was the greatest gift he would ever receive, diminished only by the knowledge that his father would no longer be accompanying him out onto the water.

He did, however, take his father with him one last time when he put it in the water that summer. With his father sitting at his side, smaller and more frail than Edward ever could have imagined him being, they cruised past many of their favorite spots on Lake Winnipesaukee that day. They put the boat in the water in Meredith Bay and cruised to Center Harbor. They made their way around Governor’s Island, past The Witches and out into The Broads, the heavy wooden hull of their small craft rolling over the swells with ease. His father took the wheel in Alton Bay, and Edward could

see the joy in his father’s eyes as he pushed the throttle forward until the boat just skimmed across the surface of the water. For a moment, as he watched the long bow cutting through the waves, he felt as if he’d leaped back in time. They were all alone out on the water, and with no reminders of the passage of time, with nothing to indicate that it was 1987, it was as if nothing at all had changed— nothing, that is, except that, at some point during those intervening years, his father had suddenly become an old man.

When they finally returned to the landing in Meredith, Edward cranked the winch and hauled the boat onto the trailer. When he stepped around to secure the boat, his father looked at him with a haunting expression that made him stop. He reached out and grasped Edward’s hand, placing it upon the smooth surface of the bow, the spray from their long journey still beading upon it. They said nothing, but they both realized that it was the final ritual they would share with the boat, and one rite of passage that Edward always wished would never come.

Edward was a competent sailor. He’d practically grown up aboard the little boat, and no one knew better than he how seaworthy it was; certainly not Gloria, who had been out on it only a handful of times, and only on the calm water of the New Hampshire lakes where she felt more comfortable.

The sight of Edward leaving the house on Saturday mornings with the Chris Craft in tow always filled Gloria with a sense of dread, especially when she knew he’d be venturing out on the ocean. She’d warned her husband repeatedly that his boat was simply too small to be cruising out on the open sea, but Edward cavalierly brushed her warnings aside.

Just one day earlier, Gloria had begged him not to take the boat out, and she warned him of an approaching storm.

“I’m just gonna get her wet,” Edward assured her. “I’ll be ashore long before that storm hits.”

The Vanishing Expert

The Vanishing Expert